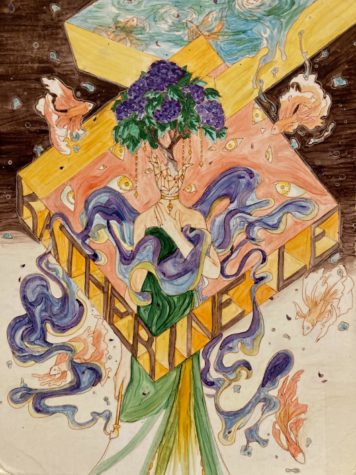

Hydrangea

Art from the Perspective of Katherine Le

Artwork by Katherine Le

November 20, 2021

What’s in a hydrangea?

A masterpiece.

The flowers blossom in Senior Katherine Le’s artwork. White. Blue. Pink. Violet.

Purity. Vanity. Sincerity. Royalty.

The various meanings of this round bundle of blossoms bleed across the page like watercolor. To some, it’s a jumble of uncertainty. Under Le’s paintbrush, it’s an isolation of meaning.

Her symbolism stands out: desire for deeper understanding.

This is something both rooted in Le’s artwork and needed to fully appreciate it.

“As a visual artist, I am particularly careful about what my work says or does for me and/or the world around,” Le says. “That doesn’t mean it has to be anything ‘life changing’, or ‘reality shifting’. If I’m being honest, sometimes I go, ‘This would look neat, let’s draw it!’ Sometimes it’s not that deep.”

Deep or not, the young artist’s work is anchored in careful research of hidden meanings, a camera roll filled with reference photos and art progressions, sketch to completion.

“But being an artist is weird because it’s subjective. Has anyone seen modern art? The ones with one line drawn through the canvas?” Le goes on. “I don’t really get it, but I think the artists that specialize in that style have a perspective that we as viewers don’t quite understand. Like I said, it’s a subjective experience.”

Le’s pencil dances the line between perception and reality.

“I often get people asking me what a certain drawing means,” Le says, “and that’s the fun part. It can mean whatever you want!”

It’s the ability of a single flower to have as many meanings as it does petals.

“Sure, there might be an underlying theme, issue, or question it’s responding to,” Le elaborates, “but ultimately, it all depends on the viewer.”

Viewing art is no more a static process than creating it is.

“How can you relate? What do you think the artist felt?” Le thinks from the mind of the art viewer, “These kinds of questions are fascinating to me. Unlike math or science where there is a single answer, art is open for interpretation.”

Le twists the threads of her ideas into a masterpiece, but it is up to the viewers to unwind this web of pencil strokes into their own thoughts.

“Because art is so subjective, it is also overlooked for its various unique qualities,” Le explains. “Many people place an emphasis on certain styles because of their tastes, and never bother to look at other styles because they simply don’t care for them.”

Art is meant for more than just a glance, and an unwillingness to unwind its intricacies frustrates Le.

“This is why I think realism is a favorite among styles, its spoon-feeding information to the viewer essentially,” Le says. “There’s nothing wrong with that of course, but it pains me to see viewers write off art for being too ‘vague’ or ‘confusing’, write it off as mediocre, and walk away.”

It is not just walking away from paper and lead and paint. It is walking away from the mind of the artist as it is shared with the world.

“Every piece starts with an idea. What do I want to say? How will I express it?” Le considers her artistic process. “This doesn’t have to be a solid idea; it can be as loose as an emotion.”

Le works less in pencil than thought, less in paint than emotion.

“Once the intent is pinned down, the process of creating a piece will vary from moment to moment: draft, finalize, execute.” Le relives the flurry of movement needed to capture an idea, “Over and over, I run through drafts and ideas, take into consideration composition, color, and many other factors, until I polish that concept into a finished product.”

But is art ever truly finished?

“It’s difficult to decide when a piece is finished, but I find that if I can look at a piece for a couple days without worrying about its appearance, it’s as good as it’ll get,” Le concludes.

Perhaps, this is where the breath and heartbeat of a masterpiece is first found: under the pair of eyes of its first viewer, the artist.

“To me, an artistic masterpiece all depends on the artist’s thoughts,” Le says. “Of course an outsider’s opinion matters, but no one will be able to fully understand the piece better than the person who made it.”

It is in the hands of the artist that art achieves masterpiece-dom. It is under the eyes of others that it achieves success.

“An artistic ‘success’ is slightly different,” Le explains. “This almost implies that the art had a specific purpose it accomplished to perfection: to impress, to report, to recount. It’s a slight difference, but I can’t say that the implications are exactly the same.”

An artistic success that lingers in Le’s mind is ‘Can’t Help Myself’ by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, a piece that doesn’t stand in the Guggenheim Museum but moves. The industrial robot of stainless steel and rubber bleeds onto the white floors of its box, and cleans it up, bleeds, and cleans, bleeds…

“I remember getting chills watching the robot arm struggle to scoop up its mess in a never-ending loop.” Le says, “It all felt so futile. Although I could only watch through a screen, the piece felt just as powerful, as if I were standing right next to it.”

As kin to reason and emotion, thought and impulse, art may appear less a web of intricacies and more a knot of confusion, but, in the end, it is simply art.

In the end, it is not the end but the process that makes art.

Artistry is “just a matter of why and how you do it,” Le says.

With care? With thought? With emotion? As a hydrangea yearning for a deeper understanding?

“I love the freedom of expression it allows me to wield,” Le concludes. “A piece won’t ever look the same for me as it does to others. And that’s part of the beauty.”