Masterful Storytelling: Shifting the Lens of Perspective

There is something every cinephile knows; good films aren't made by their story, but rather how they're told.

February 28, 2018

Christopher Nolan, Warner Bros.

Nolan’s display and use of perspective to revolutionize storytelling is worthy of a bow.

Spoilers of Christopher Nolan films ahead- you’ve been warned.

“So where are you? You’re in some motel room. You just – you just wake up and you’re in – in a motel room. There’s the key. It feels like maybe it’s just the first time you’ve been there, but perhaps you’ve been there for a week, three months. It’s – it’s kind of hard to say. I don’t – I don’t know. It’s just an anonymous room.”

The narrator’s opening lines in Memento (2000) set the focus of the viewer for the rest of the film. One of Christopher Nolan’s best, it tells its story in a unique way. Rather than playing out the scenes in chronological order, it begins with the end.

In each scene, you wake up with Leonard, the film’s protagonist, and are confused as to what’s happened previously- just like he is. This is because Leonard was injured in an attack on his wife and himself and left with no long-term memory, removing his ability to live normally. This unique twist on the “I don’t remember the past but I’m trying to find X’s killer” cliche brilliantly turns the film into a spectacular and thrilling experience that consumes your thoughts after it’s over and begs you to watch it again.

Nolan is known for telling stories out of chronological order, but he doesn’t always just play with time. He shifts the perspective of the viewer and shows the perfect elements from the right character to put them in their shoes and tell their story honestly, exactly like the character feels it. In Memento he does this by leaving the viewer as clueless as Leonard, and thus we empathize with his situation so much more.

In Interstellar (2014) the traditional protagonist is Cooper, an old pilot who missed his chance at going to space. The film follows him as he gets another chance, and not just traveling to space this time, but saving humanity from the dying Earth. But Cooper isn’t really the hero.

Two other characters are arguably the true protagonists of the story, Murphy, Cooper’s daughter, and Dr. Brand (the young one). And that’s the part of the brilliance of Interstellar. Instead of simply following the characters as they save humanity, we watch Cooper as he figures it out and plays his part in the overall effort. We see that it’s Cooper’s love for Murphy and Brand that transcends the dimensions and allows him to send the necessary information back to Earth to help Murphy save the people there.

Inception (2010) is another classic Nolan film. And again here we see another exemplary example of why the story isn’t as important in making a great film but rather how the story is told. Inception’s plot at the surface level is fairly easy to follow and make sense of. Essentially, Cobb has been hired by a man named Saito, to plant the idea, in the mind of a young Robert Fischer, to dissolve his late father’s goliath company. We follow Cobb as he goes deeper and deeper into dream worlds and learn more about his past along the way.

The debate about the film is: in the end is Cobb in the real world or still in a dream? This may seem somewhat basic, however, the way this is conveyed through Cobb’s eyes brings an incredible amount of depth to the story. Nolan has stated in interviews that the film is intentionally left ambiguous, as to let the viewer decide how the movie actually played out- but I would make a different argument. Reality, the way we view it, is ultimately subjective to the viewer. And from Cobb’s ending in the film, happily reuniting with his children, the message is that to him- it doesn’t matter anymore.

Nolan also has a habit of playing with the viewer, and misdirecting their attention to hide things within his films. In Inception he does this at the very end. The last shot of the movie focuses on the spinning top on the table, and so that’s what the viewer watches too. But the audience has been misdirected into thinking that the spinning top is the key to determining whether Cobb is still in a dream or not- but they miss the point entirely.

What’s important is Cobb in the background running to his children who finally turn around and greet him. Cobb doesn’t watch to see if the top falls or not (if it did or didn’t it wouldn’t matter because it’s not a reliable totem ((a totem is a device that tells the person who owns it if they’re in a dream or not)) but that’s for another article) because Cobb doesn’t care if he’s in a dream or not anymore, he’s happily reunited with his children. Real or not, Cobb has accepted the illusion of reality and is content with what he’s got.

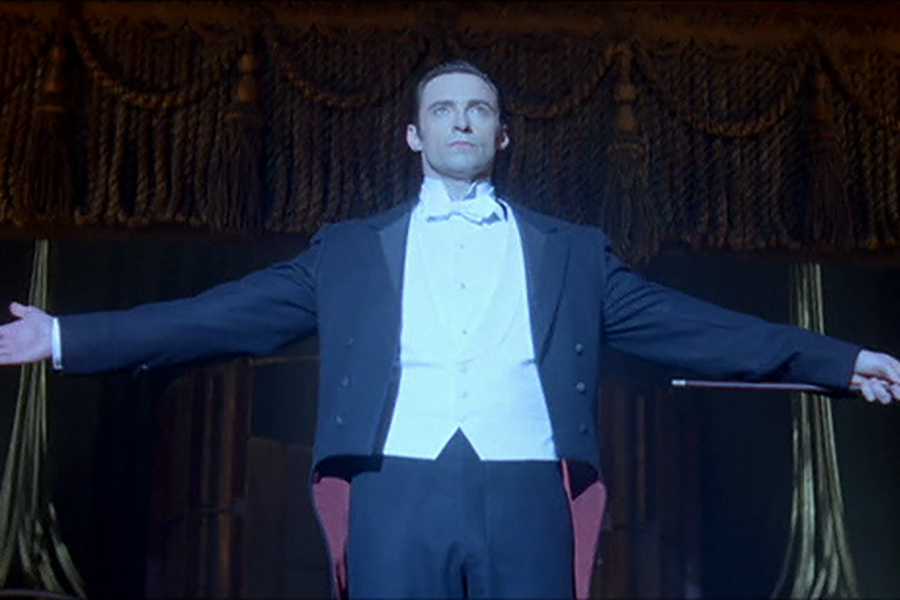

The Prestige (2006) is perhaps Nolan’s best film, and it plays with the audience the most. It’s the tale of a rivalry between two magicians, played by Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale, that quickly turns deadly.

In The Prestige, Robert Angier (Jackman) and Alfred Borden (Bale) are former partnered assistant magicians. After an accident leaves Angier’s lover dead, they have an escalating feud that the film primarily focuses on for it’s duration. While the ending is fairly easy to figure out before it occurs, it’s actually given away in the opening scene, but most viewers weren’t “watching,” and don’t “really want to know,” as Cutter, Angier’s manager and engineer, would say.

Nolan plays with time again in The Prestige. The first half of the movie is Borden in prison reading a diary of Angier’s as he read’s Borden’s diary from some years ago. That coupled with showing scenes in precisely the perfect order and manner to disguise the secrets of the film make it an enthralling experience for the viewer and leave it marked as a must re-watch.

“Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called ‘The Pledge’. The magician shows you something ordinary: a deck of cards, a bird or a man. He shows you this object. Perhaps he asks you to inspect it to see if it is indeed real, unaltered, normal. But of course… it probably isn’t. The second act is called ‘The Turn’. The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. Now you’re looking for the secret… but you won’t find it, because of course you’re not really looking. You don’t really want to know. You want to be fooled. But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough; you have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call ‘The Prestige’.”

Cutter’s lines at the beginning pave the way for brilliant irony through out the rest of the movie. It can’t be understated how astutely he calls out the audience for something they’ll do before they even know they’ll do it. One of the grievances people have with The Prestige is that the last 30 minutes of the film are too predictable, but Nolan already acknowledged that people would have this response in the movie itself.

Borden has lines where he states he would never give up the secret to his magic tricks, because once people know the secret and how the trick is done they don’t care anymore. This is exactly what the audience does. As soon as they know the twist ending they lose interest and think the movie is just predictable and boring. The self-awareness Nolan shows is nothing short of absolute brilliance.

Throughout all his films, Nolan displays the same sense of awareness in knowing who and what to show the audience, and how to shift the lens of perspective to create a thought-provoking classic movie.